Two officers walk into the Federal building, one carrying shackles as they go about their day. It is unknowable whether they just returned from detention operations, or if they are on their way to detain the next group. (Jonathan Chang)

By Jonathan Chang

Jonathan is an independent photojournalist based in San Diego. His work focuses on social movements and the fight for democracy. His Venmo can be found here.

It’s about time I work on the “journalism” in “photojournalism.” I am stepping out from behind the lens and sitting behind the keyboard. On December 5, I went to the Edward J. Schwartz Federal Building in San Diego to photograph an immigration story sweeping the country and San Diego in particular. San Diego has some of the highest ICE arrests in the country.

Previous visits to the San Diego Federal Building went as expected. As I would state my purpose with security guards at the entrance, they would scan my camera. I would walk through a metal detector and make my way into the building. The most recent day was different. This story is not about immigration, it is about freedom of the press and government censorship.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated. Your one-time contribution is appreciated. Donations are always welcome, there is no paywall.

Your contribution is appreciated. Your one-time contribution is appreciated. Donations are always welcome, there is no paywall.

Your contribution is appreciated. Your one-time contribution is appreciated. Donations are always welcome, there is no paywall.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearlyI approached the same entrance as normal. I had press credentials from the San Diego Police Department around my neck, camera strapped across my body, and had my driver’s license ready to present.

This time I was not granted access to the building with my camera. I was pulled to the side by two security guards from Paragon Systems, the firm contracted to provide security for the Edward J. Schwartz Federal Building. I was told I could not enter with my camera.

Most of my interactions were with Guard S. Elomrabi; I did not get his first name. I asked if I could take pictures with my cell phone. Elomrabi said I could. When I asked him the difference between a camera and a cell phone, he did not have an answer. He kept repeating, “I just work here.”

I replied to him backhandedly, saying “I get it, you’re just following orders.” Elomrabi did not pick up on my undertone and slight.

Elomrabi asked if I would like to speak with the DHS Inspector, Officer Panama, and I eagerly agreed. A few moments later, a DHS Police Officer came out wearing a tactical vest inscribed with “DHS POLICE” in yellow. Officer Panama reiterated what Elomrabi told me. Panama never provided me with her first name. I affirmed to her I understand I could not take photos inside the courtroom. I was not going to the courtroom; I was going into the building. I told her I’d be staying in the hallways to document the story of the volunteers inside the building to capture any detentions that may happen while I was there.

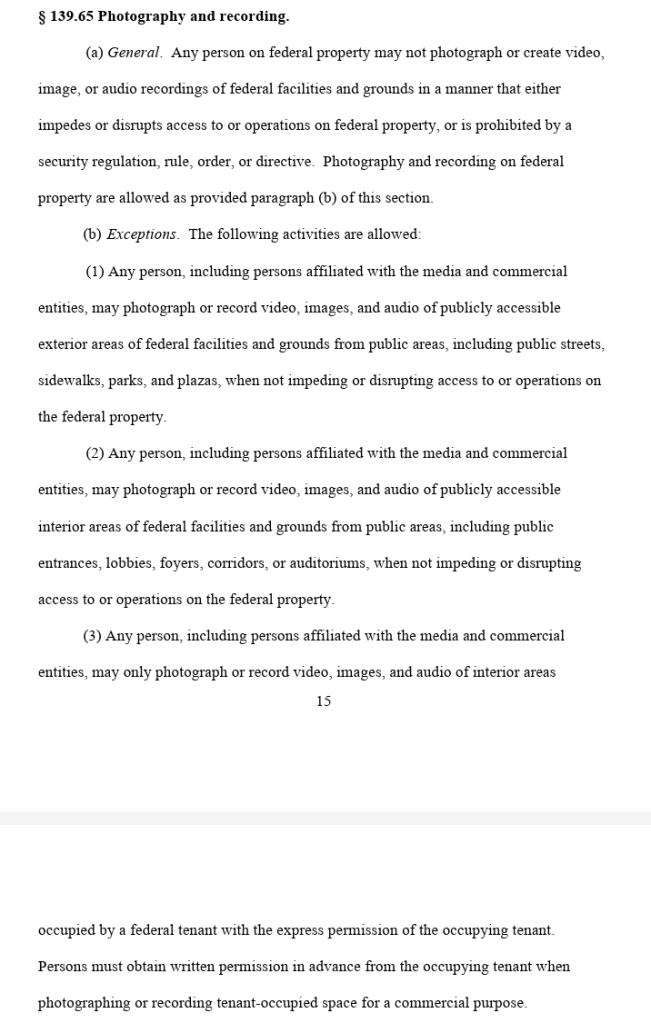

Panama told me a new policy was put in place on November 5 at federal buildings. The new policy of the Federal Building is 6CFR 139.65.

A Department of Justice (DOJ) Fact Sheet from the Executive Office for Immigration Review dated November 2025 states “Visitors are not required to check in with court personnel before entering a courtroom to observe, although the presiding Immigration Judge may ask all visitors to identify themselves at the start of the hearing.”

I was told by Panama that I could only enter with my camera with permission from a tenant in the building. Otherwise, I would have to leave my camera in my car. I asked her the same question I asked the guard, and said “besides the technical aspects and image quality, what is the functional difference between my camera and a cell phone’s camera?” Panama gave the same answer, “I don’t know.” I again retorted with “You’re just following orders?” She agreed.

I told Panama that it appears as if the government is trying to hide or create an obstacle for the press to report on what is happening in the building. New York Times photographer Mark Abramson published his work on November 8, when he was at the San Diego Federal Building covering immigration for two weeks in October. That work was done in the same hallways I was trying to access. Panama responded, telling me I can interpret it however I want.

After she left the courtyard, I looked up 6CFR 139.65 “Photography and recording”. Paragraph b2 clearly states that photography is permitted in public areas, but paragraph b3 says photography of tenant-occupied spaces must have permission.

After reviewing the codes, I wanted to address my questions again. It seemed Panama was citing paragraph b3 to me, without understanding the previous paragraph. By 11:20 AM, a second Paragon guard told me Panama was gone for the day, no one from DHS could talk to me, and only the Lieutenant from Paragon Systems was able to speak to me. That Lieutenant could not make a determination as to whether I could enter the building with my camera. It wouldn’t surprise me if she told the Paragon guard to tell me she was gone because she didn’t want to deal with me.

Further, in a November 2025 DOJ Fact Sheet from the Executive Office for Immigration Review states, “Visitors are not required to check in with court personnel before entering a courtroom to observe, although the presiding Immigration Judge may ask all visitors to identify themselves at the start of the hearing.”

What happened to me may seem minor. I am an independent photojournalist and my camera was turned away. That’s exactly why it matters.

It is the right of the public to know and see what is happening in their name. Incidents like this are a canary in the coal mine for a free press. If an independent or freelance photojournalist can be blocked without a proper explanation while wearing a press pass issued by the San Diego Police Department, that means the government can single-handedly decide who counts as press.

The First Amendment protects not only the right to publish news, but the right to gather it. Courts have repeatedly recognized that journalists must have at least the same access to public spaces as the general public. When our government restricts the press without understanding its own rules and enforcing the wrong interpretation, it creates a chilling effect on newsgathering. The Constitution was written to prevent exactly this sort of event. Freedom of the press does not depend on whether an image is captured with a camera or a cellphone; it depends on whether the public can see what its government is doing.

Could I have gone in with my cell phone and left my camera in the car? Yes. But the image quality between the two is vast. No news agency or wire service will purchase a license to a photo taken by a cell phone. The government is creating a barrier that is making it harder for journalists to do their job and report what is happening in their buildings.

The photo on the left was taken on a Nikon z6iii with a Nikkor 24-120 f/4 lens shot at 35mm f/11, no edits were applied. The photo on the right was taken on an iPhone 16, no edits were applied. (Jonathan Chang)

What happened to me isn’t about me being inconvenienced; it’s about the press at large and a government that continues to strip away access to the press. It’s about whether a federal agency can use unclear rules. It’s about federal agents who do not understand the rules they are meant to enforce.

Today it was me; who will it happen to tomorrow? The dismantling of a free press isn’t something that happens at once; it dies by a death of a thousand cuts from small unchallenged restrictions exactly like this.

Leave a comment